Robert J. Maxwell

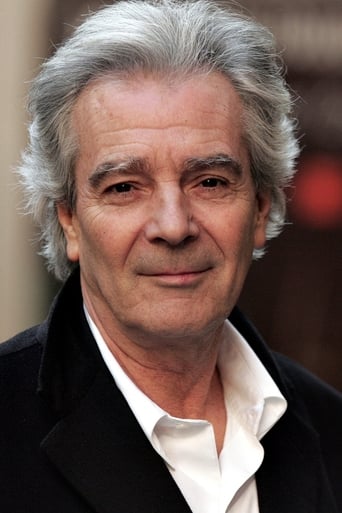

Blaise Pascal died at the age of 39 in 1662, a contemporary of René Descartes. We don't hear nearly as much about Pascal as we do about Descartes. Of course Pascal never said anything as memorable as "I think, therefore I am." But he DID say something like "the heart has its reasons which the mind will never know" and "men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction" and (my favorite)"Nature is an infinite sphere of which the center is everywhere and the circumference nowhere."It's my favorite because I don't understand it. I can't tell whether Pascal was channeling Euclid or Joseph Campbell was channeling Pascal.Of course that's neither here nor there. Pascal came from a sort of upper-middle class French family, not overly liked because its Catholocism was at the time démodé. However the kid was a genius. It's impossible to list his achievements which ranged from the material to the philosophical. He has several things named after him -- units of measurement, mathematical tricks, and the like -- and even a spiritual notion called "Pascal's choice." Pascal figured that you could either believe in God and act accordingly -- or not. If God didn't exist, the outcome would be the same, but if he or she DID exist, then believing would get you into heaven, while disbelief would take you elsewhere. I'm vulgarizing all this, naturally. For a fuller analysis, kindly read my forthcoming tome that explains everything, "I, Who Know Nothing."The movie. Made for TV although you'd never know it. The production design is exquisite. And the actor who portrays Pascal, Pierre Arditi, bears a striking resemblance to the death mask Pascal left behind. He was always sickly, and Arditi gets this across too. He's often too weak to walk unaided, and his head is declined sideway so that it seems almost to be resting on his shoulder. His sickness wasn't feigned either. Nobody's head is wrenched off, yet it's a very engaging film. Roberto Rossellini has done a fine job of directing it. No point is spelled out in capital letters but only handed to the viewer matter of factly. Did you know that Pascal built one of the first computers, a bread-box sized device that could do arithmatic up to and incuding multiplication? I didn't.

tieman64

Roberto Rossellini directed a string of biographies in the 1960s and early 70s, all of which revolved around famous historical figures (Christ, Pascal, Descartes, Socrates, St Francis, St Augustine, King Louis XIV, Giuseppe Garbaldi, and one unrealized project about Marx), and all of which utilized a sparse, stripped down aesthetic which revoked the pomp and pageantry typically ascribed to such characters.The earliest of these films, if one ignores "The Flowers of St Francis" and "Viva L'Italia" (aesthetically, they don't quite belong to Rossellini's "new phase"), is "The Rise to Power of Louis XIV", released in 1966 and funded by a French television production company (Rossellini turned to television after a string of box office flops). Starring Jean-Marie Patte as King Louis, the film begins with the death of Cardinal Mazarin, the incident which marked Louis' ascension to the throne of France. What follows is less an attempt to demystify Louis than a lesson in realpolitik. Rossellini draws parallels between kings and film directors, politicians and actors, and dwells on what he sees to be a widening gap between appearance – the calculated, outer face of power and politics - and everyday reality. And like Visconti's "political" films, "The Rise to Power of Louis XIV" is implicitly about the birth of the modern nation state, the decline of feudalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie, though unlike Visconti, who was prone to nostalgia, Rossellini adopts a more cosmic tone; he sees transience and inevitable decay in all things.Rossellini's "Socrates" was released five years later, and focuses on the philosopher's later years. Comprised mostly of dialogue, all terse and to the point, the film is Rossellini's advocation of reason and intellect, traits which themselves land Socrates in hot water, as he is put on trial and sentenced to death for "corrupting youths" and "opposing the state". Released in the midst of both Vietnam and the Cold War (and the nuclear arms race, a new age of unreason), the film is both Rossellini's attempt to put hippies and activists in togas and sandals, and a call to arms; test the Gods with a hammer, question leaders and be warned that any state which craves power will stop at nothing to maintain its grip on such.In 1972 Rossellini released "Blaise Pascal", his somewhat cold examination of the seventeenth-century scientist and mathematician. The film revolves around a court of judges, one of whom is Pascal's father, who accuse a servant of practising witchcraft. What Rossellini is really presenting, though, is the flip-side to "Socrates". Here we observe men of the state as they behave irrationally in the guise of utmost rationality. This is a cautionary tale about the death of enchantment, and the danger of cold, iron logic, which commits crimes in the guise of truth and denies a certain all-inclusiveness or subjectivity. Mirrrored to this tale is Pascal's own existential crisis, and fear of what he calls "the void of infinity". To deal with this void "we need a multitude of methods", Pascal says, which echoes the sort of "atheistic spirituality" Bergman was likewise dealing with at the time. For both directors, reason without spirit is as icy and destructive as spirit without reason (in interviews, Rossellini would cite "atheism" as itself a prejudice. What he strove for was what he called "knowledge without dogma"). The film ends with a brilliant sequence which strongly recalls Bergman's chamber pieces, Pascal "embracing" God on his deathbed, his room darkening whilst a maid lights a feeble candle.Sandwiched between "Socrates" and "Pascal" was Rossellini's "Augustine of Hippo". If Rossellini's earlier "biographies" trace the formation of the modern nation state, the rise of the post-faith moment, the dangers of subsuming all things to post-enlightenment rationality, then "Augustine" takes the next step and critiques covetousness and the "logic" of a budding, 21st century capitalism. "Tear the greed out of your heart," Bishop Augustine of Hippone preaches, as he urges his listeners to turn their backs to the "cult of the senses" and the "worship of youth". Alongside this is the film's clash between Augustine's meek band of non-violent monks and the Donatists, a group of violent "heretics" who themselves become the recipients of violence when Rome Falls. At this point Augustine urges his followers to embrace and help their Donatist foes. By the film's end, Rossellini has captured an odd paradox; mankind both torn apart by Christian morals, and dependent on Christian morals for survival.Rossellini released "Descartes" in 1974 and "The Messiah" one year later, one about seventeenth-century philosopher Rene Descartes the other about Jesus Christ, but both about quiet men of reason who advocate clarity and honesty in a world overrun by dogma. In "Descartes", such dogma spews, ironically, from men of science, all of whom are tainted by personal prejudice and bias. Science is the new faith, the new gospel, the new irrationality, Rossellini states, a problem with Descartes rectifies with his "twenty one rules", which replace Christ's ten commandments with a set of instructions designed to foster a methodical approach to testing which lessens errors, ulterior motives, preconceptions and prejudice.Meanwhile, in typical Rossellini fashion, Christ is portrayed not as a deity, but a blank slate upon which his followers blindly project their burdens, wants and needs. Rossellini's Christ is a resonant tabula rasa, and it is ultimately others who turn him into the son of God. In this regard, Christ's followers are turned into a parody of irrationality, whilst those naysayers whom films typically show lambasting Christ as a conman and charlatan, are shown to be simply reacting against illogical, scripture twisting "Christians" who are, at worst, a dangerously irrational mob, at best, actual revolutionaries.8/10 – Stiff, but great climax.