InformationRap

This is one of the few movies I've ever seen where the whole audience broke into spontaneous, loud applause a third of the way in.

AshUnow

This is a small, humorous movie in some ways, but it has a huge heart. What a nice experience.

Caryl

It is a whirlwind of delight --- attractive actors, stunning couture, spectacular sets and outrageous parties. It's a feast for the eyes. But what really makes this dramedy work is the acting.

blind_masseuse

There are definite touches of Ozu in this film, with much of the action taking place in the background or middle ground. But, it's also a film in its own right, using just the minimum of hints to make it more than just a collection random montage of scenes. It's as if we were privileged to spend an hour or so peeking intermittently into another person's life, but not really expecting to come away with a neatly packaged story, only an appreciation for life as it is. Even so, some interesting themes seem to float in and out. There is the clock/timepiece ubiquitous presence and the absence of words that is as meaningful as a whole conversation. I was intrigued by the possibility that Yoko (Yo Hitoto) felt, on a mythical level, that, like the changelings, she was switched out at birth, though it's not clear whether she felt like the baby that was kidnapped or the goblin ice-changeling left in its place. But it might explain, in a small way, why she was so determined to raise the yet-to-be-born baby on her own--she wanted to make sure that the goblins do not get a chance to switch babies this time. There are other references to fecundity and the birthing process, such as Hajime's drawings that show him as a fetus in the middle of a subway womb, holding Yoko's gift timepiece. Hajime's drawing is, in fact, an anime-like depiction of the many shots of trains pulsing around a tranquil waterway that pulsates like a watery womb, showing nothing yet of what it could bring forth--much like this film. I do have to confess that I went,"Huh?" when the movie ended. Then, that lively song (was that by Yo Hitoto--it's good?) came on, with more energy than the whole of the movie, and made me understand that I do appreciate this type of film once in a while, but not as a steady diet.

crossbow0106

How about walking into a minefield next, Mr. Director? This story, according to writer director Hou Hsiao-Hsien, is a tribute to the great Japanese director Yasojiro Ozu, (selected Ozu films that are essential viewing: Tokyo Story, Late Spring, Equinox Flower, I was Born But etc)and its about a young lady who at the beginning tells s male friend about the strange dreams she has been having. I smiled right away when the first image of the film came on, which was a commuter train. This young lady Yoko, played by Yo Hihito, goes to visit her parents and tells her mom matter of factly that she's pregnant with her Taiwanese boyfriend and has no intention of marrying the guy. Yoko then lives her life, spending time doing research with her male friend Hajime, who owns a second hand store. You can tell he likes her, and so do I. She wants to be independent. The use of trains, long shots of street scenes and a simple but intriguing plot make this an Ozu type film.While it doesn't reach Ozu's heights (that is near impossible), its very good. The consistency of mood, the suppression of emotions and the camera angles are also very much like Ozu. If not Setsuko Hara, I could see Yoko Tsukasa playing the character Yoko in this film if she was her age at the time of this film. The constant scenes of trains made me like the film even more. A very worthy effort.

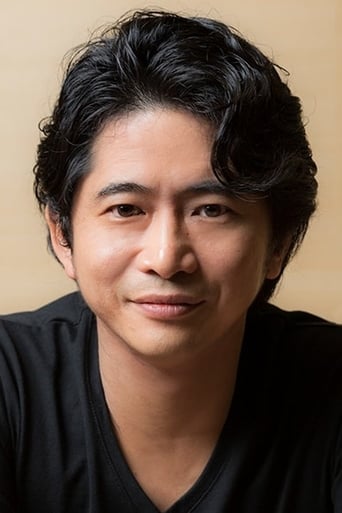

Ed Uyeshima

I am a relative latecomer to the transcendent work of film auteur Yasujiro Ozu, whose masterfully understated views of Japanese life, especially in the post-WWII era, illuminate universal truths. Having now seen several of his landmark films such as 1949's "Late Spring" and 1953's "Tokyo Story", I am convinced that Ozu had a particularly idiosyncratic gift of conveying the range of feelings arising from intergenerational conflict through elliptical narratives and subtle imagery. It is Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien's keen aspiration to pay homage to Ozu on his centenary with this generally enervating 2003 film. Among with co-screenwriter T'ien-wen Chu, Hsiao-hsien appears to get the visuals right but does not capture the requisite emotional weight that would have made the glacial pacing tolerable.The story concerns Yôko, a young Japanese writer researching the life of mid-20th century Taiwanese composer Jiang Wen-Ye in Tokyo after coming back from Taiwan where she taught Japanese. After 25 drawn-out minutes of character set-up, she reveals to her father and stepmother that she is pregnant by one of her students in Taiwan. At the same time, Yôko's coffeehouse friend Hajime, who runs a used bookstore, has an obsession for trains and seems likely to be in love with her. Hsiao-hsien connects this slim plot line with a series of shots held for inordinately lengthy takes as the frame composition changes. There are also long stretches of silence as well as an abundance of scenes featuring trains. While these techniques are consistent with Ozu's style, Hsiao-hsien cannot seem to dive into the characters' psyches the way Ozu did with maximal fluidity and minimal theatrics, in particular, Yôko's plight seems rather non-committal in the scheme of the drama presented and her parents' reaction overly passive to hold much interest. In fact, the whole film has an atmosphere of exhaustion about it, which makes the film feel interminable.The performances are unobtrusive though hardly memorable. J-pop music star Yo Hitoto brings a natural ease to Yôko, while Tadanobu Asano is something of a cipher as Hajime. The rest of the characters barely register, even Nenji Kobayashi and Kimiko Yo as Yôko's parents. Cinematographer Lee Ping-Bing provides expert work though he violates a cardinal rule of Ozu films by not keeping the camera stable during shots. Hitoto speak-sings the fetching pop song used over he ending credits, "Hito-Shian". The DVD includes an hour long, French-made documentary, "Métro Lumière", which actually does help provide some of the context for Hsiao-hsien's approach to the film. It includes excerpts from Ozu's films, in particular, "Equinox Flower", to show the parallels with this film though surprisingly no mention of either "Tokyo Story" or "Early Summer", the obvious basis for some of the scenes and situation set-ups. There are also edited interview clips of Hitoto, Asano and Hsiao-hsien, as well as the film's trailer.

danielhsf

Ozu is dead. If there's one thing that Hou manages to prove in his tribute to Ozu's centennial, it is that Ozu is dead. Never is there going to be another man who can portray human relationships in the same light as Ozu. The same steadfastness they have as they try as hard as they can to hold on to each other; the sadness they feel when having to leave the family; the difficulties of living together in one household; the moments of regret that they have when one of their family has to leave; and their final acceptance that these are all but a part of life.Hou shows us a Japan that has changed so much from the Japan that Ozu so painstakingly tries to hold on to by capturing it on his camera. Each tear, each regret, each joy is now lost in a world that tries too hard to change. Wim Wenders first laments this in Tokyo Ga on how banal Tokyo has become and how much of an imitation culture new Japanese culture is. Cafe Lumiere, while not being as impassioned as Wender's masterpiece, is every bit as pensive about its regret of the passing on of the old Japan that Ozu loves so much.While in Ozu's films, a pregnancy would herald a big event in a family's lifeline, in Cafe Lumiere it is merely a passing thought. While in Ozu's films, the lead character (most often played by goddess-like Hara Setsuko) would usually be self-sacrificial as best she can to ensure the family's togetherness, here Yoko is determined on striking out as a single mother, regardless of her father's silently burning disapproval.Undeniably, Hou doesn't pass much judgment on his characters. In fact the portrayal of Yoko only shows her as a very modern and much independent Japanese female that is fast becoming the norm in Japan. The female who does not want to be tied down and holds little regard of familial values. And definitely, it would be seen as regressive should Japan return to the past for the sake of the days when family was at the core of societal structure. After all, the definition of progress is change right? Yet, one can't help but feel the absence of Ozu in this movie, the absence that makes its tone all the more poignant in spite of its spots of warmth. Ozu seems to be like the ghost of Maggie Cheung in 2046, or the missing woman in L'Avventura; he is not there, and is never referenced in the movie, and yet, the opening shot of the movie and a few scenes of familial warmth gives one such a pang in the heart that is so distinctly Ozu. In fact, that Hou decides to have many shots of trains departing and leaving and criss-crossing each other in modern Tokyo, and letting us hear the all-familiar sounds of trains going across railways that is so definitive of Ozu's films, only shows that he is fully aware of this fact, and, like Wenders, is seeking to find what little there is left of Ozu's spirit. In the overwhelmingly modern backdrop of Tokyo, we see how something of the past, like the cafe that Yoko hunts for, that some people so want to preserve, has been turned into another urban development project. However, in the film, Hou also shows us that although the landscape of Tokyo now denies Ozu, there is still decidedly some of Ozu's warmth in human relationships. Like how Yoko still feels the same kindred spirit as she tucks in to her favorite dish that her mother has prepared; seeking out old sights in her hometown, sights that remind her of times when she was a kid and still not thinking of independence. And just perhaps, in showing all this, Hou is persuading us to accept life as what we can, just as how the people in Ozu's movies eventually have to accept the loss of one of their family members.I went to Tokyo last June and coincidentally, Kamakura was part of the itinerary. I remember how excited I was, since Kamakura was many a setting for Ozu's films, and it was the place where Ozu was buried after his death. As I reached the Kamakura station on the Enoshima metroline, my heart was all awashed with glee to see that the station looked almost exactly the same as it looked in Ozu's films. The same old signboard, and the same railway tracks against looming mountains. And yet as I walked around Kamakura (now a popular tourist spot for its famous Daibutsu or Big Buddha), I couldn't help but notice how foreign it was despite its quaint Japanese-ness. There were so many tourists walking around the town amidst its quiet surbuban houses, and so many signboards blaring English signs. In a bid to find Ozu's grave, every time I saw a cemetery I would go over to look if there was a tablet that has only a 'mu' character on it. But I never found it. Sigh.