Matialth

Good concept, poorly executed.

Nessieldwi

Very interesting film. Was caught on the premise when seeing the trailer but unsure as to what the outcome would be for the showing. As it turns out, it was a very good film.

Keeley Coleman

The thing I enjoyed most about the film is the fact that it doesn't shy away from being a super-sized-cliche;

Nicole

I enjoyed watching this film and would recommend other to give it a try , (as I am) but this movie, although enjoyable to watch due to the better than average acting fails to add anything new to its storyline that is all too familiar to these types of movies.

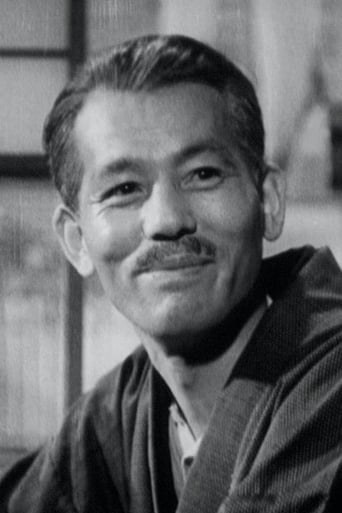

Charles Herold (cherold)

This is the first Yasujirô Ozu I've every seen. It's a beautifully made movie, but honestly, I feel like about 70% of my enjoyment of it was simply Setsuko Hara as Noriko. She is a wonderful actress who seems able to move from joy to quiet sorrow effortlessly. She can say more in silence than most actors can with pages of words.Take her away and I don't know what I would think. It would still be a nice looking movie with a reo-realist influence and a simple yet rather compelling story. But Hara is the reason I care about what happens. Some of the other actors are good (although I found the father too opaque to connect with), but no one can match Hara.My main takeaway from Late Spring is that I need to see more movies starring Hara.

Lee Eisenberg

"Banshun" ("Late Spring" in English) is the first Yasujiro Ozu movie that I've seen. If it's any indication, he's a great director. The movie focuses on the relationship between a father and daughter but in the grand scheme of things it looks at love and loss, and the general continuation of life and all things around us. Ozu made the movie in the context of the Allied Powers' occupation of Japan after the latter's defeat in World War II, and there are reminders of the occupation (such as a Coca-Cola ad). The father's insistence that his daughter get married reflects the new path that the Land of the Rising Sun would have to take now that its empire was gone.Although I'm not familiar with Ozu's work beyond this, I could detect some things that he did here. There were some low angles to simulate point of view shots, and what are called "pillow shots": a single shot or multiple shots of objects employed to transition between scenes. There's also a scene of a vase, and I understand that Ozu featured such a shot in every one of his movies. The vase could represent stasis, creating a contrast with the movie's theme of change (inherent in its season-themed title). And then there's the question of tradition. The daughter is supposed to get married, but she has been resisting this: the general continuation of things might not last. Because of this, one interpretation is that the movie is a critique of marriage.Whatever the case, I hope to see more of Ozu's work. I'll probably have to see the other installments in his Noriko trilogy first.

chaos-rampant

Ozu by now had reached a sublime maturity in his eye. This flew in the back of two decades of film work of course, it's why I think Ozu continued in the silent format longer than his peers, slowly evolving that eye. The achievement is not in any impeccable composing he does, I'm not interested in an aesthetic look of him. I'm for looking for images that vibrate with a more fleeting sense of life that hides in them, that Buddhist nothingness or nonself that is Ozu's gravestone message (the ideogram "mu" is inscribed there).The film is all about the inevitable necessity of having to go, about separation and stepping out on your own for the long journey of life. In a slightly different context it would have been about death. Here it's marriage, the daughter having to abandon the idyllic childhood home where she lived with her father for so long and open up to the world.I'll keep with me two marvelous scenes that encapsulate this: at the shrine near the end where father and daughter are waving to each other from opposite banks of a stream, and back in their room as they pack up their things and prepare to go, it's as if a last farewell is understood, quietly hanging in the corner of the room. All you need to know is right there in these scenes, powerfully conveyed with resonance, each one a parting memory.On the other hand a forward-looking sense about the future is missing in the girl, an even mildly curious excitement as ambiguous counterpoint to the sadness, something constructive about the journey ahead. Leaving her simply crushed and resigned that she must go gives me a somewhat unpleasant sense, an almost neurotic childishness in the character. Here I encounter again Ozu's persistent flaw from previous films, made all the more obvious because he is so refined by now in every other respect. The realization of why she must go doesn't spring from inside, it does not dissolve visually in the air. It comes in a long instructive speech by the father. Ozu's eye is clear, the story is lucid flow. But the deeper point is resolved as ordinary drama, from the outside.This makes me all the more curious about his next films in this his more celebrated period. These flaws are interdependent, inner realization in the story and wholly cinematic brushstroke from it. Both are a matter of meditating, of embodying the insight rather than saying it out loud. So it might be that this is only the first step of a larger journey about a character like Noriko, that Ozu grows himself as he looks to sculpt a more effusive insight about being. The titles of some of his later films imply a connectedness. I pick up the thread there.

Robert J. Maxwell

The director, Yosujirô Ozu, had a reputation for never moving his camera. I didn't notice movement in "Tokyo Story" but wasn't looking for any. This time I tried to keep track of any camera movements, not including source motion, as when the camera is fixed to a moving train or a bicycle. I only counted one. For a few seconds, Ozu's camera trundles along behind a couple riding bicycles down a lonely road. There are times when the camera remains stationary after the actors have left the screen. I began to wonder if maybe Ozu didn't know HOW to move the camera in a mechanical sense, hand-held, dollies, and so forth. But then I recalled that in Peter Yates' "Bullet" there was only one dissolve, and all the rest of the editing consisted of cuts.Okay. So it's a matter of personal style. And I'll take this opportunity to advise anyone who enjoys movies like "The Bourne Ultimatum" to avoid "Late Spring" at all costs. If they were to try sitting through this movie -- a little grainy, in black and white, with Japanese subtitles, subtle, and an immobile camera -- the results might be tragic. They should remember that a person in shock should be placed in the Trendelenburg position with the feet elevated between 15 and 30 degrees above the head.The movie? Oh, the movie. We get to meet a beautiful and expressive Japanese woman of twenty-seven years (Hara) who lives with her fifty-six year old father (Ryû) and takes care of him. She's perfectly happy with the arrangement and so is her father, until a relative suggests that a marriage be arranged between a nice young man and Hara. Being married when you're almost thirty is rather a late spring.Well, Hara has a smile that lights up a room and a nature that complements it. But when her father brings up the prospect of marriage, her face falls and her animation bleeds out of her. It isn't so much that she doesn't want to be married. It's that she desperately wants to continue living with Ryû. He can't care for himself. "He burns his rice." Carl Jung would introduce the Electra complex at this point but I think we can safely skip it.She and her father take a vacation to Kyoto, where we see some impressive scenery, man-made and natural, which resemble picture postcards, given the immovable camera. Father and daughter have a long talk and Ryû, whose conversation so far has mostly been limited to "Hmmm", which carries several meanings, tells her that happiness is the result of time and effort, that he didn't love her mother when they were married, and that in fact he's decided to marry a woman who is an acquaintance himself, so Hara has nothing to worry about. She still has doubts but now she has hope too.But Ryû has lied to her. There is no marriage in his future. The young couple are married and leave. After the reception, Father has a few cups of saki and walks home. Sitting alone in the now quiet house, he begins to peel an apple. It's a long, single peel that finally drops to the floor, bringing back some jokes that Hara used to make about not being able to slice pickled radishes. Ryû sits for a moment before dropping his gaze. It's a touching moment because, for the first time, we realize how much unspoken love he felt for his daughter, how much he will miss her presence, the weight of his sacrifice, the bleakness of his own future.All of which goes to demonstrate that you don't need to wobble the camera around in order to make a gripping film.