Teringer

An Exercise In Nonsense

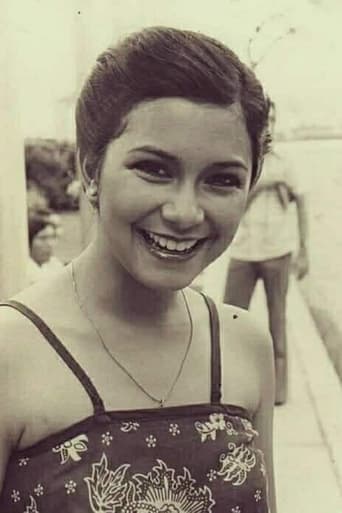

Ariella Broughton

It is neither dumb nor smart enough to be fun, and spends way too much time with its boring human characters.

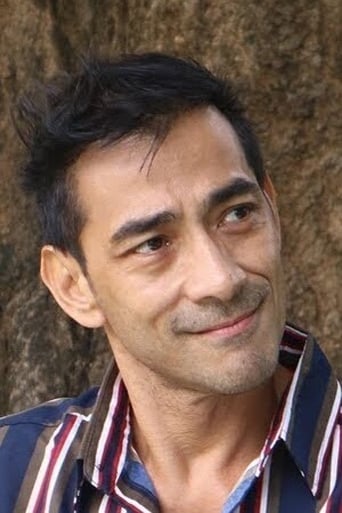

Lachlan Coulson

This is a gorgeous movie made by a gorgeous spirit.

saint_sara

Tatarin is nothing compared to Nick Joaquin's Summer Solstice. Dina Bonnevie is dull and lifeless, nothing like the original Doña Lupeng, who jumps out of the page with an almost contemptuous sort of passion. Edu Manzano could have been replaced with any other actor who can pull of a gruff, patriarchal frown. Additional story lines are added to make the plot more complex, but only serves to prolong an already tedious movie. Instead of exploring the magic of the Summer Solstice, the film rides on the heaving bosoms of Rica Peralejo and Patricia Javier, Raymond Bagatsing's buttocks, and incessant moaning and groaning of an entire horde of women.

Noel Vera

There are at least three entries in the 2001 Metro Manila Film Festival that seem meant to be taken as actual quality fare: Tikoy Aguiluz's "Tatarin" (Summer Solstice); Joel Lamangan's "Hubog" (A Woman's Curve), and Marilou Diaz Abaya's "Bagong Buwan" (The New Moon).The standout by far among the three, I think, is Tikoy Aguiluz's "Tatarin." Based on Nick Joaquin's play "Summer Solstice," the film is about the oldest and longest-running war known to man, the war between the sexes. Joaquin's problem then was how to make this war relevant again to jaded audiences (the play was written in 1975); his solution was to set the play in the 1920s, when male-dominated Western Culture was just beginning to tremble. Aguiluz's adoption of Joaquin's stratagem is, I think, a smart move--this way he captures the very roots of the war (or at least of the 20th century edition of the war) as waged by our grandparents and great-grandparents; he photographs the combatants at a time when the battle is still urgent and raw, the stakes desperately high.And the battle lines are drawn, of course, around a married couple—Don Paeng and Dona Lupe Moreta (Edu Manzano and Dina Bonnevie), on the evening of the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist, on the third night of the "Tatarin"--a pagan ritual where for three days out of the year women hold ascendancy over men.I can't think of a better Filipino filmmaker than Aguiluz to evoke the living past--especially in a production like this, where immersion in a long-gone age is crucial to the success of the film. Combining the considerable resources of Viva Studios (which are usually poured into banal glamour productions) with his keen documentary filmmaker's eye, Aguiluz (with the help of production designer Dez Bautista) evokes the remarkably authentic, miraculously detailed world of the Moretas--from the flour mill that produces their dried noodles, to the 1920s-style kitchen hard at work on dinner, to the luxuriously appointed family mansions with their incredible painted ceilings. And it's not just a matter of having an enormous production budget; it's the intelligence to pick out this particular detail, the wit to shoot from that particular angle--then the judiciousness to cut it all up so that you only glance at the images, and are left wanting more.But more than the ability to recreate a historical period, Aguiluz (again, with the help of writer Ricky Lee and editor Mirana Medina) is able to streamline Joaquin's play, to focus on the struggle between Don Paeng and Dona Lupe. The three have tinkered with Joaquin's married couple, made delicate adjustments, crucial revisions--the Moretas, for one, have lost all warmth and affection for each other, where in the play they still show signs of tenderness. Don Paeng has become a psychologically immobile, sexually impotent monster (kudos to Edu Manzano for the courage to portray such a thoroughly unlikable man) while Dona Lupe (Dina Bonnevie, in possibly the performance of her career) has become more submissive, more withdrawn (the better to highlight the climactic reversal when it comes).Then there is the dialogue, which has been pruned, made less explicit, made more functional than decorative. Besides the careful pruning, Aguiluz manages to locate the drama in the moments when words are not spoken--through shots that encapsulate in a single image the tension of the scene, like the one where Dona Lupe's foot is kissed by Guido (Carlos Morales), with Don Paeng watching from the balcony. Don Paeng, the shot says to us, is ascendant by virtue of his standing in the balcony, but is also rendered remote and helpless by the distance.Then the "Tatarin" ritual itself. Moved offstage in the play, the ritual occupies center stage in the film: a wordless, ten-minute orgy of pulsing drumbeat, flaring torches and convulsing women. Aguiluz wanted the sense of a real location turned theater set, and he got it--the dance, staged at the foot of an actual balete tree, feels nightmarish, surreal. And obscene--though nudity is at a minimum, there is no lack of lewdness to the drumming and dancing, which at times is reduced to frank rutting. "Pagan" is a polite and inadequate term for what happens at the foot of the balete tree."Tatarin" feels more lighthearted than Aguiluz's earlier works, if only because he doesn't end the film with a life-or-death situation (meaning: the protagonist didn't die). More, it's the first really comic film Aguiluz has ever directed, and he handles the material with admirable lightness and vigor. One of the best Filipino films of the year, and my vote for best of the festival, hands down.

clarencehenderson2003

HALO-HALO CULTURE AND PAGAN RITES Set in the 1920s, the film tells the story of a couple caught in the juxtaposition of Catholic/Hispanic value systems and the pagan rituals that existed long before Magellan set sight on Cebu. The Tatarin is a uniquely Filipino version of a druidic rite. During this surreal ritual, which takes place during the feast day of St. John the Baptist, normally repressed women transform themselves into "Tatarin" - enchantresses and witches. They gather together to worship the centuries-old balete tree, which sets them totally free from inhibitions, empowering them to dance erotically while the men (who normally per macho Hispanic tradition completely dominate them) watch helplessly. Symbolically, this suggests a theme of balance, with man as Sun and woman as Moon - and about the imbalance brought about by the externally imposed values of the West. The ritual reflects, like many pagan rites, the vital importance of maintaining balance between heaven and earth, an essential balance for ensuring healthy lives, avoiding devastating wars, and raising good children. When things get out of balance, terrible things happen. In pre-Western Philippines, the Sun (male) represented the Supreme God (known by Kabunian and other names). But equally important was the feminine moon, wife of the sun. The cycle of sun and moon ensured balance, much as yin and yang do in other Asian traditions. These dichotomies are captured elegantly in Tatarin, which has as one of its primary themes an oppressive heat symbolizing elemental passions always on the verge of exploding. The movie has many images of the sun boiling in the day and the moon burning hotly during the night. There is a great deal of repressed libido here, captured in the Filipino term libog, which basically means the state of being horny. Paeng, the masculine and aloof husband (played by Edu), sees the ritual as silly and old-fashioned, suitable only for the indios. His wife, played by by Dina Bonnevie, embraces the ritual as a long-sought after channel for self-expression (and orgiastic release), something totally foreign to Catholicism and the repressed sexuality it brought with it. Ultimately, Paeng ends up crawling in the dust in front of his wife, ready to kiss her feet now that she has finally asserted herself as a woman. Aside on libog: When asked to interpret his work, Joaquin reportedly replied: "It's all about libog, isn't it?" To illustrate the use of the term, consider the following three versions of the phrase "you're making me horny": Tagalog: Nalilibugan ako sa iyo; (2) Taglish: You're making me libog naman; (3) English (sixties version): Why don't we do it in the road?

LitoZulueta

FAMILIAR TERRITORY by Lito B. Zulueta, Published in Philippine Daily Inquirer, January 7, 2002Some of the currency of public affairs journalism that flavors "Hubog" and "Bagong Buwan" is used to some ironic effect in the period drama "Tatarin," Tikoy Aguiluz's filmization of Nick Joaquin's short story "Summer Solstice" and play of the same title. Aguiluz really returns to familiar territory here: he achieved renown in the 1970s when his short film on the Mt. Banahaw rituals won an international prize. In fact, "Tatarin" achieves a mesmerizing effect in the mountain ritual parts that provide the viewers the special feel of religion with their strange brew of mysticism and pre-literate hysteria.Aguiluz's documentary flair is used to remarkable effect here. If he's guilty of embellishment and sensationalism, as in the sex scenes, he can be forgiven because he portrays the battle of the sexes, resurgent matriarchy, male insecurity, the clash between the old and modernity-interweaving themes in Joaquin's fiction and drama-with the detachment of a scientist or even a journalist. Among the films of the Metro Manila Film Festival 2001, "Tatarin" is really the most realized, without even a mere tokenism to global cinema. It is the movie that is most faithful to its material and vision.